In considering a framework for research into wellbeing and developmental outcomes of young people, in the context of their relationship with social media, Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological system (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Bronfenbrenner & Crouter, 1983; Bronfenbrenner & Morrris, 1989) provides a useful perspective. Given the ubiquity of the media and young people’s seeming immersion in it, the significance which Bronfenbrenner places on daily or “molar” activities is particularly useful. In outlining, for instance, how “molar” activities are a reflection of development, differences in age, gender, context, time and place are focused on. Indeed, when considering development, how it is influenced and what it influences, ability, skills, behaviour, relationships and the development of identity all have a place.

A key concern of social media researchers in the last few years, for example, has been “time spent” using social media. Time is seen as a useful metric by which to make assumptions about associations between platforms and the psychosocial lives of users. If we take an ecological perspective, “molar” activities, which necessarily include social media use, are both a cause and a consequence of development. Young social media users reason, decide and choose how to spend their time and these decisions are based on their goals, interests and temperament. Not only this, but these decisions are not made in a vacuum, the young person’s context, family situation, social relationships, all play significant roles in time spent, whether use is active or passive, skilled or not. Additionally, Weisner (2002) identifies dimensions of activity settings where the culture of young people emerges; these could also be included in this ecosystem. These include others who are present when the activity is occurring, what the activity is, why and how the activity is carried out.

Bronfenbenner allows us to see young social media users situated in a multi-layered context. From here we see users subject to influences that operate in their daily lives; from immediate to more abstracted contextual forces. The context in which the young user moves, is seen as a process, rather than an a processor. So, when we consider time as a metric to examine associations between social media use and wellbeing or developmental outcomes, not only would age and gender be considered, but recognition would also be given to the social class (what type of equipment or connectivity the user can afford), the device, the connectivity provided, the affordances and constraints of the life of the young person, who is being connected to and when, where these connections are being made and why and, importantly, what type of activity is occurring. If this were not complex enough, the ecological system requires us to think of the bidirectionality of contextual influences. So, rather than imagining social media users as passive recipients of content and being effected, we see them actively shaping their social media experiences, the social media landscape and consequently, their development.

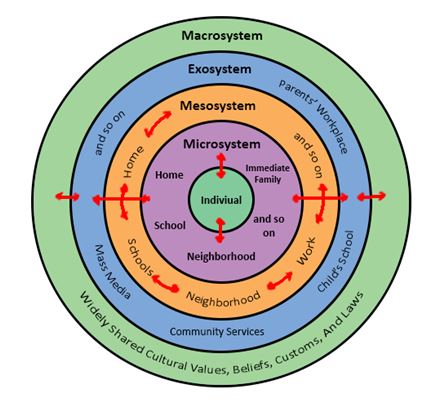

Figure 1: Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model.

Bronfenbrenners Ecological Developmental Model frames thinking about young social media users, consequences of use and interactions with other systems in the ecology.

Microsystems: The young social media user (individual characteristics, personality, temprament) sits at the innermost level of the system. This system involves interactions with peers, family, education provider and neighbourhood. Positioning internet technology, social media or different platforms here, helps to consider user/family, user/peer, user/school, user/platform contexts when thinking about wellbeing or developmental outcomes. We can also imagine interactions between this level and other levels. Furthermore, when one considers that each social media platform offers the user different social media experiences, with different affordances, one could imagine discrete microsystems for each platform.

Mesosystems: At the meso level, connections with other social contexts are made. At this level, those from the user’s microsystem interact with other nodes of influence; a friend may attend a different school or college and interact with others who do not belong to the user’s network. Similarly, parents, teachers and other influential adults within the microsysytem can interact with each other, bringing back to the microsystem artefacts of those interactions, thereby influencing interactions within the microsystem. It is easy to imagine Facebook “friends” interacting with others in their own separate social networks.

Exosystems: Young people are often effected by influences which are outside their control and experience. In the exosystem influences like parental employment, school internet policy, and government regulation will effect social media use and the outcomes. For example, the type of technology available to the young person, if not in employment, is dependent on the employment status of a parent and if they can afford to purchase a smartphone or afford high-speed broadband. Government policy around availability of certain platforms effects usage and effects; certain governments restrict access to Facebook, WahatsApp etc., while others provide citizens with unlimited, free highspeed broadband. Both of these policy decisions effect users.

Macrosystems: At the more abstract level, wellbeing and developmental outcomes can be influenced by the legal, political and regulatory systems along with the values within the community, attitudes and norms. Importantly, again here, one should remember the bidirectioality of the ecological system. So, norms, attitudes, and values of a young social media user are influenced by others, but the norms, attitudes and values of young people can, in turn, influence others.

An ecological perspective highlights the complexity of researching wellbeing and developmental outcomes of social media. Importantly, this perspective also reminds us to consider proximal or more distal variables, how young people interact with other systems and, we are obliged to be cognisant of the bidirectionality of those interactions. Finally, when thinking about adaptive and maladaptive consequences of social media use, larger (government policy or platform developer ethical standards), abstract (societal values and attitudes), and sociohistorical systems (the changes that occur inside and outside the young person’s life over time) have a place in discussions.

References

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. (1998). The ecology of developmental processes. In: Damon W, Lerner R, editors. Handbook of child psychology. Vol. 4: Theories of development. Wiley; New York. pp. 999–1058.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Crouter, A. (1983). The evolution of environmental models in developmental research. In: Mussen P, editor. The handbook of child psychology. Vol. 1, Theories of development. Wiley; New York. pp. 358–414.

Weisner, T. (2002). Ecocultural understanding of children’s developmental pathways. Human Development, 45, 275–281.