We live in an age of unprecedented intimacy with computer technology. Aside from computers at school, at work and at home, an increasing number of us are tethered to omnipresent smart devices. This is certainly true for the current cohort of young adults. In the U.S., in 2014, 85% of young people aged 18-24 owned smart devices (Nielsen, 2016), while in Ireland, RedC reported in 2012, that 65% of the emerging adults owned a smart phone (RedC, 2016); by 2014 this had increased to 85% (Thinkhouse, 2015). It is estimated that young Irish internet users spend up to six hours per day connected to devices (IPSOS/MRBI, 2014), with three hours spent social networking. And “we are not alone”. According to GlobalWebIndex, in 2014, the average global user spent more than 6 hours online, compared to 5.5 hours in 2012; almost 2 hours were spent on social networking compared to just 1.5 in 2012.

How do you spend 2 hours a day on social media? Well, it was found that, in the U.K., young people perform “checking behaviours” on smart devices up to 85 times per day (Andrews et al, 2015). That’s a start.

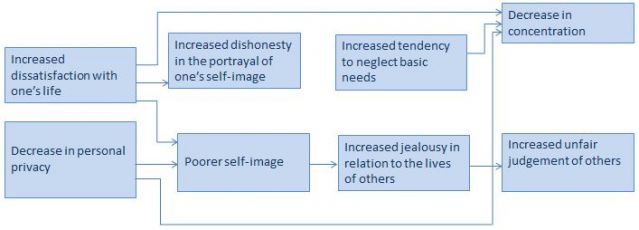

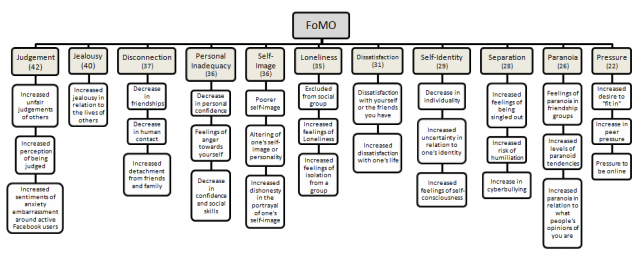

Research into young adults and their use of social media paints a partial and fragmented picture. Studies generally correlate social media use with outcomes such as self-esteem (Valkenburg & Peter, 2011), grade point average (Kirschner & Karpinski, 2010), emotions (Bevan, Pfyl, & Barclay, 2012), mood (Sagioglu & Greitemeyer, 2014), life satisfaction (Krasnova, Wenninger, Widjaja, & Bruxmann, 2013), social comparison (de Vries & Kühne, 2015) etc. Researchers reveal a host of undesirable social, emotional and behavioural consequences; decreased motivation (Flanigan & Babchuk, 2015), poor academic performance and psychosocial maladjustment (Cerretani, Iturrioz, & Garay, 2016), envy and depression (Appel, Gerlach, & Crusuis, 2016), body surveillance and appearance comparisons (Tiggemann & Slater, 2013), and cyberbullying (Gahagan, Vaterlaus, & Frost, 2016). That said, social media has also been shown to have positive consequences for the user; positive psychological and physiological experiences (Mauri et al, 2011), belongingness (Nadkarni & Hofmann , 2012), relationship formation and maintenance (Ellison et al, 2007), enhancing self-esteem (Gonzales & Hancock, 2011), reaffirming social bonds (Knowles et al, 2015), and socialisation functions (Barker & White, 2010), have all been related to social media use.

Important and all as these findings are though (and they are), it has been argued that the scope of this research is limited, that gaps exist in the current understanding, and with new platforms appearing regularly, with changing features and design, more integrated research examining the positive and negative consequences of social media use is required (Caers et al, 2013). Moreover, there have been calls for research that provides a coherent understanding of the drivers and the positive consequences of social media use; research which explores how “social media experiences” stimulate, help young people establish and maintain relationships or provide optimism (Finkelhor, 2014). Given the levels of engagement and immersion, and given that we have only gained an incomplete, disjointed understanding of the consequences of the social media experience, it is vitally important, particularly for young people and their development, that we gain a complete understanding of the broad range of positive and negative, social, emotional and behavioural outcomes of use.

Studies in the social media arena reveal a clear picture of the assumptions made by researchers. Research tends to be survey based, cross-sectional, conveniently sampled and correlational. Concepts, constructs and definitions are driven by adult researchers with limited knowledge of the lived experience, and whose interests do not necessarily coincide with those of the user. Participants, by virtue of having been born between certain dates are assumed to be “digital natives”(Prensky, 2001); uniformly familiar with, reliant on and immersed in internet technology. Simply being a member of a social networking site but not knowledge of what features of the site one is using, is enough to qualify one for inclusion in studies. Interestingly, comparisons between users and non-users are rarely, if ever, made. The list goes on! And these shortcomings have consequences.

Cohen (1972), said that “moral panic” occurs when a group in society is portrayed in the media as representing a threat to the norms, practices and values of society. The behaviour of this subgroup is sensationalised and magnified by its portrayal in the media. Public discourse around the behaviour is driven by the media, without regard to the actual “panic” being experienced, or evidence to support the phenomenon. Indeed, since this definition was offered, a new and worrying trend has emerged; sensationalist interpretations and dissemination of scientific or pseudoscientific findings by popular press. In this regard, the negative effects of social media use by young people is well publicised, with articles, based on findings like those mentioned above, appearing almost daily in mainstream media warning of the dangers of use, of excessive use, of “addiction” or of particular platforms.

Technological ingenuity and its evolution increasingly effects how we interact with each other, and as a collective. The social, emotional, behavioural and broader cultural consequences are just beginning to be felt. With our increased engagement with and exposure to platforms and their content, digital media is changing us, individually and organisationally, and young people are at the vanguard of that change. On-line surveys and correlations are no longer good enough, nor is it good enough for us to assume that all young people are “digital natives”. It is now time that research exploring the new hyper-connected landscape and its inhabitants reflected these changes.

To situate research findings in the world of the user, cognisant of the fact that she is using dynamic, evolving media, in a socially connected environment, novel research methods are required. First though, we need to examine the assumptions underpinning young people and their status as “digital natives”. Is mere membership of a social networking community enough to draw conclusions about the psychological state of the user? Secondly, I would argue that we need contextual, user-defined examinations, combined with research and theory, to provide us with accurate information. It is no longer adequate to correlate the use of social media with complex psychological constructs using online, self-report surveys; publication of this type of research is misleading. Certainly, taking into account the perspective and social interactivity of young people; the shifting, dynamic landscape of social media and that fact that users experience both positive and negative consequences, will ensure that correct, appropriate and relevant information enters the public domain.